Introduction

When managing infrastructure-as-code using Terraform, the state file is a key component, as it keeps track of what resources are associated with your configuration and how they are configured relative to one another. Teams will suffer from corrupted state and conflicting updates if they are left on their own to store and coordinate state.As teams compete for overall dominance, resources are neglected.

One of the primary mechanics to prevent these issues is state locking – making it so that only one Terraform operation can modify state at a time. On AWS this used to be done by using Amazon S3 (for the state file) and DynamoDB (for the lock). Terraform itself has also now added native S3 lock support, so you no longer need a DynamoDB table for locking.

Table of Contents

What is state locking and why does it matter?

- Terraform keeps its model of your infrastructure in a state file (usually terraform.tfstate). The file tracks resource IDs, attributes, dependencies, and much more.

- When different people or CI/CD processes share a remote state, however, there’s no coordination between them so they may both apply changes at the same time. That can lead to:

– both read the same old value, update it in conflicting ways.

– one write overwriting another’s changes

– corrupted or failed leading to the potential of drift or worse.

- By the law of State locking A State lock prevents concurrent writes: the first process “acquires” a lock, reads state, applies changes to it, then write back state and “releases” the lock. Still others wait or they don’t, and die when the lock does.

- When working in a team environment (with multiple engineers, or automated pipelines) state locking is not optional if you want secure, repeatable infrastructure changes.

Are you looking for data engineering solutions that scale while aligning technical execution with real business outcomes?

The “old” method: S3 + DynamoDB locking

How it worked

- S3 is utilised as the remote backend: Terraform uses a designated S3 bucket and key to store terraform.tfstate (as well as potentially workspace-specific variations).

- You use a partition key like LockID to generate a DynamoDB table (like terraform-locks).

- In your backend configuration you specify something like:

- At run time:

- Terraform writes an entry in DynamoDB (conditional write) in an attempt to obtain the lock.

- If it is successful, it reads the state from S3, calculates the plan, and makes adjustments.

- Terraform updates S3 with the new state.

- Terraform deletes the DynamoDB item to release the lock.

- Another process will either fail or wait if it tries while the lock is in place.

Strengths

- Great: DynamoDB offers strong consistency and conditional writes, you can implement robust locking

- Ideal for larger teams or high concurrency workflows.

- Known and accepted practice.

Limitations

- Needs one more AWS resource (the DynamoDB table) to configure, maintain, secure and cost-control.

- That’s more IAM permissions to grant (in S3 and DynamoDB) and more moving parts.

- A bit more complicated to bootstrap (create bucket, table), and migrate from local-state.

- Locks can become orphaned and need to be manually unlocked if mis-configured (timeout, permissions).

The “new” method: Native S3 state locking

What changed

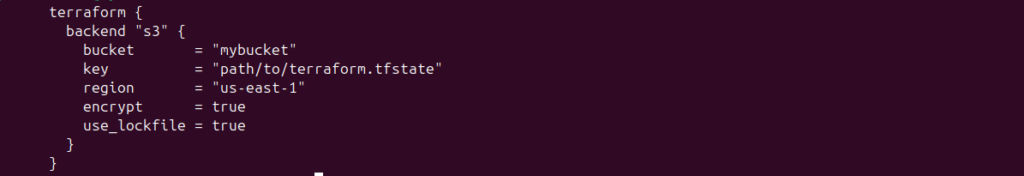

- For terraform, the backend S3 now has a new setting use_lockfile = true that allows to lock in s3 only.

- Now, you don’t have to rely on a DynamoDB table for locking – Terraform has an S3 object (a “lock file”, like `…/terraform. tfstate. tflock) for coordination.

- This is now justifiable as S3 now has stronger consistency guarantees (read-after-write) and conditional writes (so “only create this lock object if it doesn’t already exist”).

How it works

- In your backend config:

- At runtime:

- Terraform attempts to lock with the creation of a lock object (path/to/terraform. tfstate. tflock) in the same S3 bucket with a unique name and conditional write “create only if not exists”.

- If the creation completed lock obtained. Otherwise the lock is held by a different process, and Terraform either waits or exits with failure.

- Terraform pulls down state file from the S3 bucket, calculates a plan and then makes changes.

- Terraform writes the new state to the S3 object at the location given by key.

- Terraform removes the lock file (. tflock object) to unlock the lock.

- Should the process fail without a chance to delete the lock file you might have do it yourself (e.g., terraform force-unlock).

Benefits

- Simplified architecture: Only S3, no DynamoDB table, fewer moving pieces.

- Less expensive, fewer resources to track and maintain.

- Simpler configuration, less IAM permissions to set up.

- Particularly appealing for smaller teams or installations with fewer bells and whistles.

Considerations

- Because the feature is relatively new, you will want to thoroughly validate it in your environment , especially if you have high concurrency or complex automation pipelines.

- You still must make sure that your S3 bucket is properly configured (versioning, encryption, permissions) because the state file is still important.

- You’ll also need to manually deal with the unlocking if locks get orphaned (the lock flag doesn’t get removed).

- Bigger organizations who already use DynamoDB locking might need a migration path of some kind.

Side-by-side comparison

Here is a practical comparison to help you decide between the two approaches:

| Feature | S3 + DynamoDB (Legacy) | S3 Native Locking |

|---|---|---|

| Lock storage | DynamoDB item | .tflock object in S3 bucket |

| Additional AWS resource | Yes – DynamoDB table | No (S3 only) |

| Setup complexity | Higher | Lower |

| Cost | Extra cost for DynamoDB reads/writes | Minimal (just S3 operations) |

| Dependencies / maintenance | More moving parts | Fewer dependencies |

| Maturity / adoption | Long-established | Relatively newer |

| Ideal for | Large teams / high concurrency | Smaller teams / simpler workflows |

Why this change matters

- Operational overhead: Less AWS services and IAM roles leads to more simple setups, fewer mistakes, and less operational burden.

- Cost Effectiveness: Save from DynamoDB Table operations (even though its very minimal) and it’s provisioning/throughput.

- Agility: It reduces friction for teams to spin-up new environments(dev/test).

- Future proofing: Also for full dislosure, the dynamodb_table argument is deprecated in the S3 backend documentation , so future versions may exclude these.

- Migration signal: For those of you that have been using the old table based locking approach, this would be a good time to consider whether or not it makes sense for you to move over to native S3 locking.

When should you not switch (yet)?

- And if your team has an extremely high degree of concurrent Terraform operations (or many many pipelines/users) and you’ve already optimized DynamoDB locking with advanced patterns like timeouts or monitoring you may still want to stick with the tried-and-true.

- If you have a complex custom locking logic (across accounts, some external tools that are building on top of the lock table in DynamoDB) migration could require you some more work.

- If your company requires full audit/ logging of lock operations (ie: via DynamoDB logs) , then you’ll want to investigate how S3 lock files will work in with this.

- If you’re on a version of Terraform that does not yet have complete and native support for S3 locking (versioning, compatibility).

Next steps for readers

- Audit your existing Terraform backend config: Are you using dynamodb_table? Would you be willing to entertain use_lockfile = true?

- Make sure your S3 bucket is versioned, encrypted and has good IAM policies (this is important whether we’re talking DynamoDB or native S3).

- Plan a test migration path: can we try native S3 locking in non-prod, observe behavior etc.Once all are implemented and the plugin is wired up to use this new architecture. So, if something goes wrong during implementation, we won’t proceed to next step.

- Monitor your Terraform version and AWS provider version for compatibility checks.

- Keep an eye on your team’s workflows If state locking with native S3 is running properly, plan for full migration to S3 If not, you may continue using the current approach while evaluating the performance.

Conclusion

State Locking is the first principle of safe, multi-user Terraform usage. The AWS landscape is going to change: whereas one needed a separate DynamoDB table, henceforth we can do everything within S3 with native locking. For many companies that translates into reduced complexity, cost saving and easier architecturial design. However, the legacy DynamoDB approach is sturdy and understood making it a perfectly valid option, especially in mature or high-concurrency setups.

References & sources

- Official Terraform documentation: S3 backend – state locking.

HashiCorp Developer – https://developer.hashicorp.com/terraform/language/backend/s3

- Terraform backend configuration overview.

HashiCorp Developer – https://developer.hashicorp.com/terraform/language/backend

- AWS Prescriptive Guidance: Terraform backend best practices.

Amazon Web Services – https://docs.aws.amazon.com/prescriptive-guidance/latest/terraform-aws-provider-best-practices/backend.html

Related Searches – DevOps as a Service Provider | AWS Database Migration Services | Data Engineering Company in India

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Does native S3 locking require me to immediately cease using DynamoDB?

No, native S3 locking is not required. You can proceed if you already have a functional S3 + DynamoDB setup that satisfies your requirements. However, you should think about a migration strategy because Terraform’s S3 backend documentation deprecates the dynamodb_table option.

Q2. Which Terraform version is required for native S3 locking?

Native S3 state locking is available in Terraform versions that support the use_lockfile = true backend option. The feature was first introduced as experimental around version 1.10.0 and became generally available in later releases.

Q3. During migration, is it possible to simultaneously activate native S3 locking and DynamoDB locking?

For transition safety, you can temporarily set both dynamodb_table and use_lockfile = true in your backend configuration.

Q4. What should I do if a lock file (.tflock) in S3 is abandoned (orphaned)?

If Terraform force-unlock is supported, you can use it or manually remove the lock file from the S3 bucket. Before forcing an unlock, always make sure you know who is holding the lock.

Q5. Does native S3 locking alter the IAM permissions I require?

The state file and the lock file (lock file *.tflock, for example) still require S3 permissions (s3:GetObject, s3:PutObject, and s3:DeleteObject).